by

Russell Hartenberger

January 2014

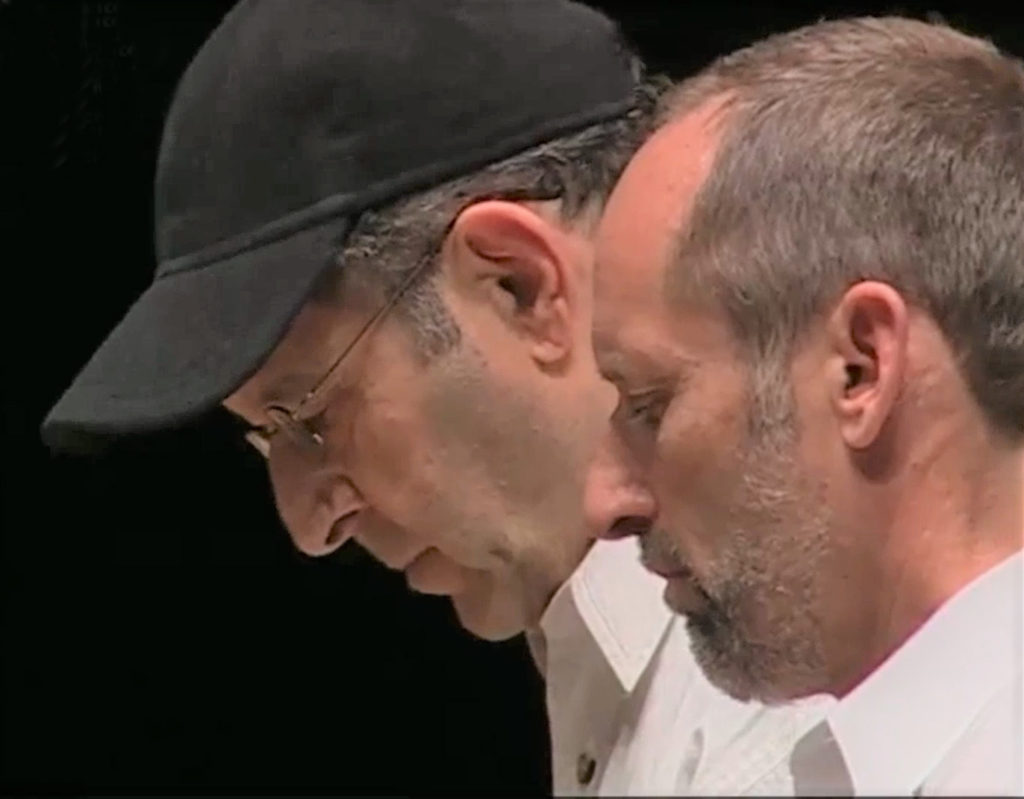

Jim Preiss studied percussion at the Eastman School of Music with William Street. Jim told me that Mr. Street was not a didactic teacher, but taught through example, emphasizing sound production and musicianship. Jim was an experienced mallet player when he arrived at Eastman and Mr. Street encouraged him to hone those skills while teaching Jim “to play from the heart.” Upon graduation from Eastman, Jim joined the United States Marine Band as timpanist and xylophone soloist. After his discharge from the band, Jim moved to New York City and entered the master’s degree program at the Manhattan School of Music where Paul Price was the head of the percussion department. While a student there, Jim began a series of lessons outside the school with Fred D. Hinger, who at that time was timpanist in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Jim said these lessons transformed his concept of playing. Mr. Hinger’s ideas about touch and stroke influenced Jim to develop his graceful style of playing with full tone and picture-perfect upstrokes.

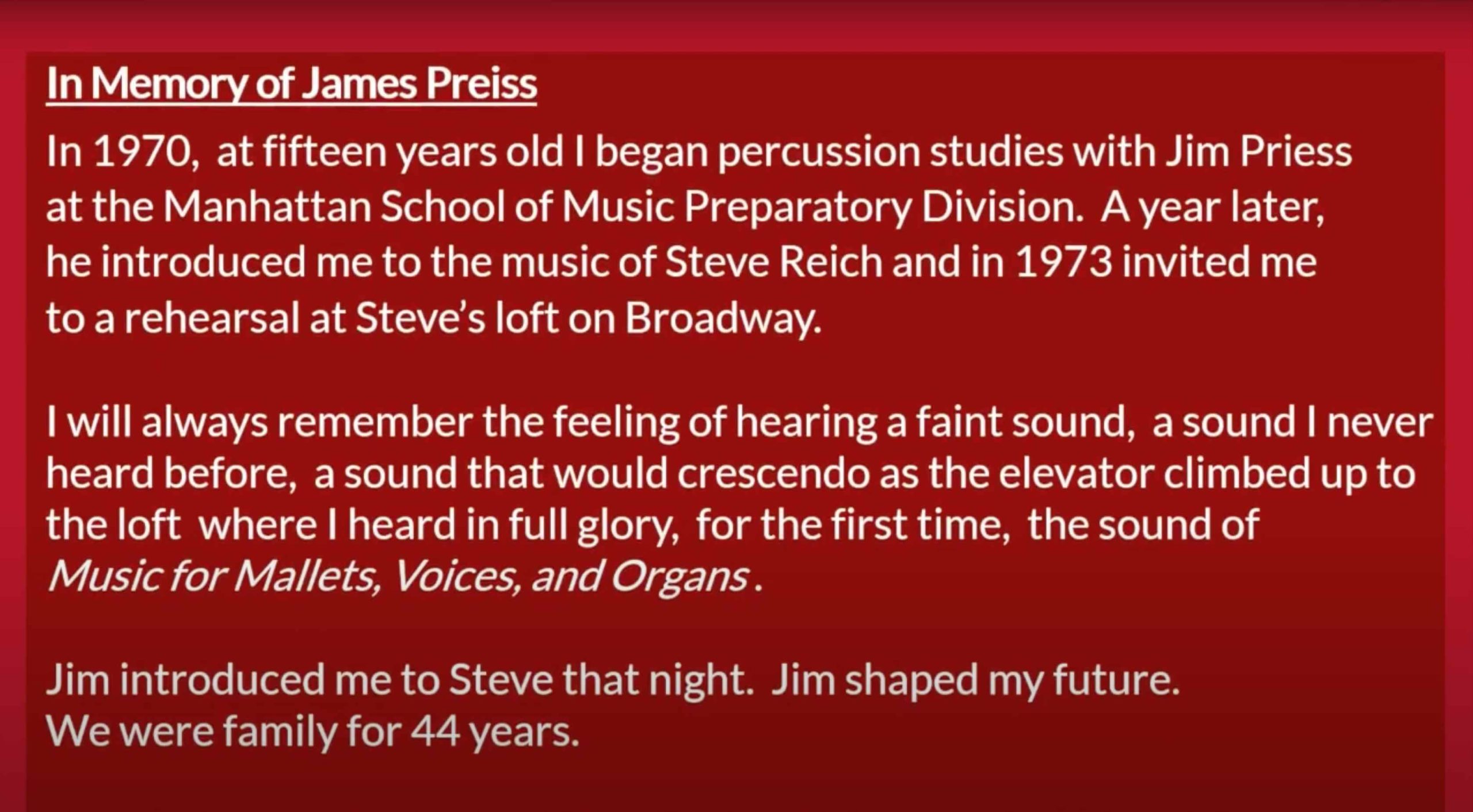

After receiving his degree from the Manhattan School, Jim joined the faculty there as one of the percussion teachers. When Steve Reich called Paul Price in the summer of 1971 to ask about percussionists who might be interested in attending rehearsals for Drumming, Mr. Price recommended Jim. At that time, I was the only schooled percussionist in the ensemble other than Steve Reich himself. So, Jim and I became the first two core percussionists in Steve Reich and Musicians. Jim and I played in the premieres of Drumming in December of that year, beginning a musical association and personal friendship with Steve and the other musicians in the ensemble that has continued throughout our lives.

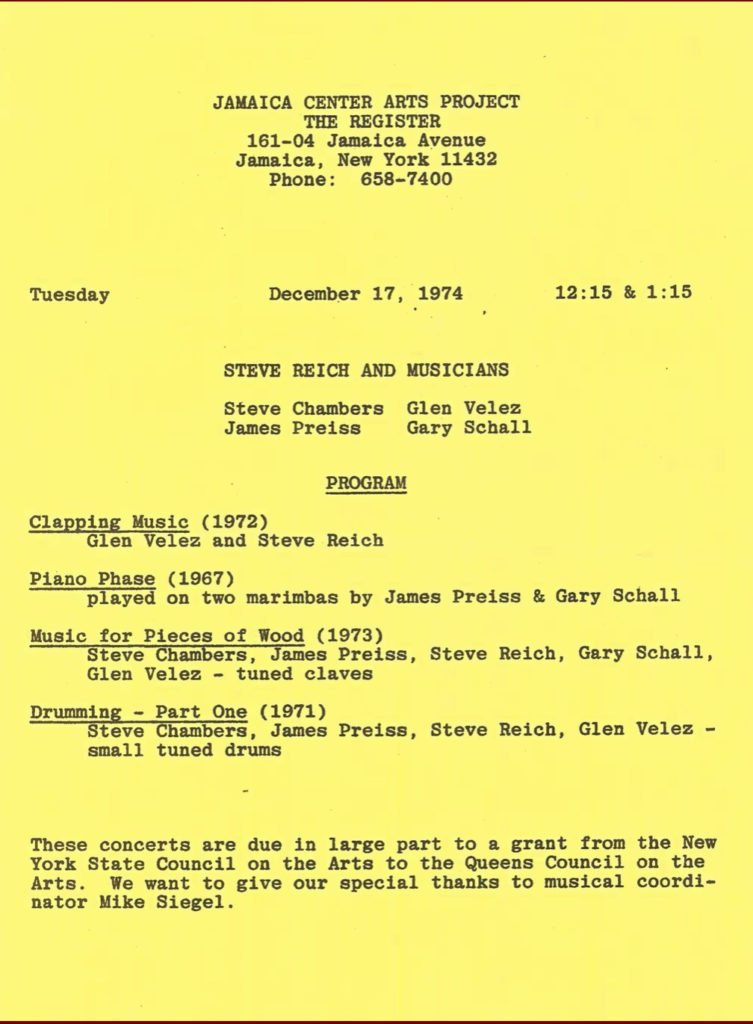

Jim brought many of his percussion students into the Reich ensemble over the years, including Gary Schall, Glen Velez, Thad Wheeler, Bill Ruyle, Kory Grossman, Richard Schwarz, and Bill Trigg. Jim and I are responsible for bringing Steve’s attention to the possibility that Piano Phase could be played on two marimbas. At a break in a recording session at a BBC studio in London, Jim and I began noodling around with the Piano Phase patterns on a couple of marimbas, realized we could play the piece, and thought it sounded good on marimbas. We played it for Steve who liked our version, and now it is standard repertoire for percussionists around the world. Jim formed the Manhattan Marimba Quartet with his students, Bill Trigg, Bill Ruyle, and Kory Grossman. It was Jim’s suggestion to Steve that Six Pianos could be played on six marimbas, thus creating another great work for percussion.

Jim was a wonderful marimba player, and in 2007 he recorded three of the unaccompanied J. S. Bach cello suites for BMP records. In the liner notes for the CD, Jim wrote:

“My deep and abiding interest in the music of J. S. Bach began during my undergraduate days at the Eastman School of Music when my teacher, William Street, encouraged me to go to the Sibley Music Library to find suitable materials for practicing to help develop my reading skills on marimba and with other keyboard percussion instruments. My idea was to start with the first book on the shelf and see how far I could get. The first category turned out to be “Music for Violin Solo Unaccompanied” shelved alphabetically. There weren’t many volumes under “A” and soon I began the “B”s. BACH turned up very quickly and I observed that there were many volumes of a work entitled Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin. I checked out one of these editions, took it up to my practice studio, and began playing the first page, the Adagio from the G Minor Sonata. I was amazed. I had never heard music quite like this before. I soon abandoned my (shelf-) reading project in order to devote more time to these remarkable masterpieces. I also became aware of the collection of suites for Solo Cello and these two volumes have been my constant musical companions ever since.”

Jim played with many groups and orchestras in New York City. He was principal percussionist of the Brooklyn Philharmonic, the American Composers’ Orchestra, the Westchester Philharmonic, and the Riverside Symphony. He performed regularly with the Orchestra of St. Luke’s and the American Symphony Orchestra and was a founding member of the Parnassus Contemporary Chamber Ensemble. He taught at the Manhattan School of Music and later at the Mannes College of Music. Whatever the situation, Jim played with the highest standard of performative and musical integrity.

Excerpts from Performance Practice in the Music of Steve Reich by Russell Hartenberger (used by permission of Cambridge University Press).

I continued rehearsing with the ensemble until I left for Ghana in May. When I returned later in the summer, Reich told me that while I was away, he had contacted Paul Price, head of the percussion department at the Manhattan School of Music, asking about percussion players who might be interested in playing in his group. Price gave Reich the name of James Preiss, who had recently completed his master’s degree at the Manhattan School and who was now on their faculty. Reich called Preiss and invited him to rehearsals, and Preiss became the next percussionist to join the ensemble.

Weekly rehearsals continued throughout the fall, usually on a weekday evening and most often on a Tuesday or Thursday. We learned the marimba, glockenspiel, and final sections to Drumming as Reich composed them and taught the parts to us. As indicated in his daily agenda entries, Reich arranged for separate vocal rehearsals to work out the resultant patterns for the marimba section and the final section of Drumming. He recorded all the rehearsals, and at the extra rehearsals, Reich, along with the singers, would choose the patterns they liked and write them down. At the full rehearsals, the singers, using microphones, sang through the chosen patterns making sure they felt right with the live sound of the marimbas. Sometimes each of these resultant pattern sections would be rehearsed for quite some time as Reich would stand back and listen and occasionally make changes to the patterns or balance the overlapping of the three voices. The singers, unlike the percussionists, used notation when they sang resultant patterns for rehearsals and continued to use notation in performances.

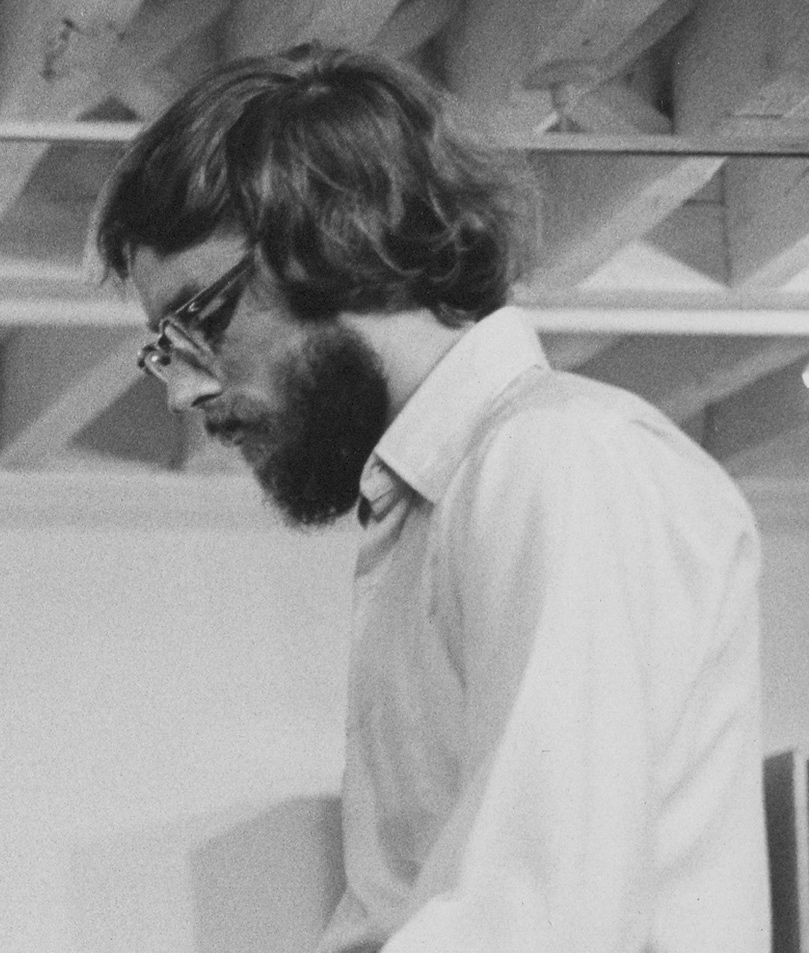

Preiss and Reich refined the resultant patterns on bongos during these rehearsals by trying out patterns and deciding which ones they found most interesting and musical. In the rehearsals and early performances of Drumming, Reich sang resultant patterns in this part of the piece, alternating or blending his patterns with Preiss, who played them on the bongos. Reich would move to one of the microphones when he sang, or on subsequent tours if we were performing the bongo section alone, he would position a microphone near the bongos. (pp. 13-14)

The percussion part assignments in Drumming, as we played them in the Reich ensemble after percussionists began playing all the percussion parts, are slightly different from those indicated in the Boosey & Hawkes score. When Reich, along with Marc Mellits, wrote out the score so the piece could be more readily performed by other ensembles, he distributed parts in the way he considered most efficient rather than the way we traditionally performed them in Steve Reich and Musicians. Reich generally assigned the parts he considered most prominent to Bob Becker, Jim Preiss, and me. These parts became associated with the people who regularly played them and were referred to by that person’s name. This is especially true of the bongo parts in Drumming. None of us (including Reich) has ever known what the drummer 1, 2, 3, 4 references are in the score. When substitute players played with the ensemble, or when I have played the piece with other groups of people, we always referred to the parts as “Jim’s part,” “Steve’s part,” “Bob’s part,” or “Russell’s part.” Our various personalities seemed to get embedded in these parts, too. Becker played the steady part during phases and is the person who determined tempos in future compositions. I did most of the phasing in the bongos and throughout the rest of Drumming and became associated with that technique. I also played the build-ups and deconstruction. Preiss played resultant patterns with his graceful, upstroke approach. He also played the third phase in the piece and is the player who doubled our parts so we could change our sticks back and forth between the hard and soft ends. Reich did a bit of everything: he played the build-ups and deconstruction with me; he sang and played resultant patterns (although he stopped singing the patterns after a few years); he played the second pair of phases in the latter part of the section; and he gave cues for all the changes. (pp. 50-51)

Reich and Preiss decided on the resultant patterns in the bongo section of Drumming during the early rehearsals of the piece. Reich sang some patterns and alternated or blended with Preiss who played other patterns on the drums. Preiss’s approach to playing the resultant patterns was a subtle one. He began with an extremely light touch on the drums and gradually increased his dynamic until the ear heard the fragment of the composite pattern he was emphasizing. His decrescendo was smooth so that it left listeners still imagining the resultant pattern even though he was no longer playing it. Preiss’s resultant patterns were a combination of short patterns and longer ones that sometimes extended over more than one cycle of the basic pattern. Occasionally, he would make a four-cycle phrasing group with the patterns.

At the end of the second group of resultant patterns that Preiss played, he often ended with a portion of the rhythm that Becker was playing. He would follow that by entering in unison with Becker and phase. I suggested to Preiss that he morph the resultant pattern into the unison entrance and then make the phase, and he was able to do this in a way that made a beautiful transition into the phase.

In the early performances of Drumming, Preiss would occasionally make up bongo resultant patterns on the spot since that was Reich’s original intention. As Becker and I became more comfortable with our parts and began to play more strongly, he stayed with the pre-set resultant patterns. Preiss felt that if he knew exactly what he was going to play he would not have to pause and try to figure out a new pattern; this enabled him to participate equally and contribute to the strength of the performance. (pp. 53-54)

Restaurant selection, of course, was an important preoccupation of the ensemble while traveling in Europe, especially in France. Once, as we drove our truck and van through the French countryside on our way to the next gig, Reich happened to read in his Guide Michelin that there was a starred restaurant not far from our route. It was lunchtime, so we drove off the highway into the small town where the restaurant was located. It was a lovely, rustic place with sawdust on the floor and a casual atmosphere. We all sat at a long table and began reading the menu. Most of us decided to order full meals, taking advantage of a rare opportunity to eat at a Michelin-rated restaurant. Jim Preiss, however, ordered an omelette à la norvégienne, which he assumed was some kind of omelet. Reich asked him if he was sure that was all he wanted since the rest of us ordered multi-course meals. Preiss said he wasn’t too hungry and that an omelet would be enough. The lunch orders arrived for those of us who had requested full meals, and we all dove into our food with gusto. Preiss sat patiently until the kitchen doors suddenly swung open and a waiter emerged with a spectacular Baked Alaska. Everyone in the restaurant gasped in unison and broke into applause as the dessert was placed in front of Preiss. Unphased by this unexpected treat, Preiss, who had already gained a reputation for having a sweet tooth, ate the whole thing himself. (p. 24)

Following a concert at the Hayward Gallery in London, we had a recording session of Drumming at the BBC. Preiss and I spent time during a break by jokingly playing the parts of Piano Phase on two marimbas. We soon realized it not only worked well but had a clarity of articulation that the piece did not have when played on two pianos. Reich heard us experimenting with the piece and liked what he heard. We soon began playing this marimba version regularly on concerts, usurping the programming of the piano version. Reich called the marimba version, Piano Phase “played on two marimbas,” but percussionists referred to the piece as Marimba Phase. (p. 26) [Note: see my article titled Marimba Phase/Mallet Phase in the Articles section of the DRUMMINGat50 website for more details.]

After the concert and recording session in London, the ensemble traveled to Bristol and Oxford for concerts. Driving anywhere in England where every driving maneuver for North Americans is counterintuitive is always a challenge, but we managed to adapt. Looking at a map for this trip, we noticed that if we altered our route somewhat we could drive to Amesbury and visit Stonehenge. Reich suggested we all get up early in the morning and drive to Stonehenge so we could be there for the sunrise. He decided on a departure time that would ensure we would be there in time, but Preiss felt it was too early and wanted to leave a half-hour or so later. After some discussion, it was decided that the group would leave early in the van, and that Preiss, who was traveling with his wife Donna, would leave in the truck at the time he thought was sufficient to be there for the sunrise. So the group left early the next morning in the van, drove to Stonehenge, parked, and started wandering around the stones in the early dawn. (In those days, visitors were allowed to walk within the stone arrangement; today they must stand behind a barrier.) After some time, the sun started peeking over the horizon and casting light on the stone pillars. Just at that moment, the truck with Jim and Donna Preiss appeared on the road into Stonehenge, perfectly timed so they would arrive just as the sunlight shone through the stone monuments. We all laughed and cheered at Preiss’s impeccable sense of timing (to go along with his unerring sense of time) as he and his wife joined us to watch the sunrise over Stonehenge. (p. 26)

The Six Marimbas version of Six Pianos came about through James Preiss and his association with another percussion group in New York City, the Manhattan Marimba Quartet. The group was comprised of Preiss plus three other free-lance percussionists, Bill Ruyle, Kory Grossman, and William Trigg. The Manhattan ensemble wanted to play the piece on six marimbas and approached Reich with their suggestion. Reich liked the idea and, in collaboration with Preiss, rescored the piece using mode and key changes to avoid unmanageable mallet positioning and make the piece more playable on marimbas. Whereas the three sections of Six Pianos are first in D major, second in E Dorian, and third in B natural minor, the Six Marimbas rescoring is first in D-flat major, second in E-flat Dorian, and third in B-flat natural minor. Bob Becker and I joined the Manhattan Marimba Quartet in the first performances and the Nonesuch recording of Six Marimbas. (pp. 179-80)

by

Gary Schall

In Spring of 1971, I walked into the percussion studio, Room 612 of the Manhattan School of Music, for my Prep Division audition, and at that moment, for the very first, time shook hands with James Preiss. It is said that first impressions are everlasting. All of Jim’s friends, former students, and fellow musicians are connected through a similar first encounter – an everlasting impression, a handshake, the hands and touch of a remarkable man.

A brilliant musician and teacher, Jim created a circle of influence that was profound. All those who knew him through music were drawn into the realm in which he lived – one of great artistry, sensitivity, and spirituality. Jim’s magical touch, his sticks which became the extension of his hands but even more an extension of his heart and soul, and his expressive articulation of the turn of a phrase, were part of his spiritual journey. They were reflected in all the lessons he taught to hundreds of students at Manhattan School of Music and to thousands of musicians who performed with him over the years.

During a lesson in my senior year of high school, Jim told me in great detail all about an amazing dinner he had the night before. He was taken out by the first student of his to graduate from the Manhattan School. Everyone knows Jim’s passion for food and his even greater passion for talking about food. If Jim had been born fifty years later, he would probably be called a Hipster, and I’m sure he would be considered a Foodie as well. Hearing his excitement over this meal, I wanted to take him out to dinner to celebrate my graduation from high school. Instead, my Mom and Dad insisted that Jim and his wife, Donna, come to our house in Brooklyn for dinner. It was first of many, many meals enjoyed together and the first of many meaningful moments continually shared with our families.

The next meal was at Jim and Donna’s apartment at 3111 Broadway. Donna baked incredibly delicious bread and mid-west style desserts – all unforgettable. Together, they provided me, as a teenager, with such an important lesson – one of commitment, marriage, and eternal love. After their son, Jeff, was born, I was their first babysitter and even watched Jeff the night their second son, Chris, was born.

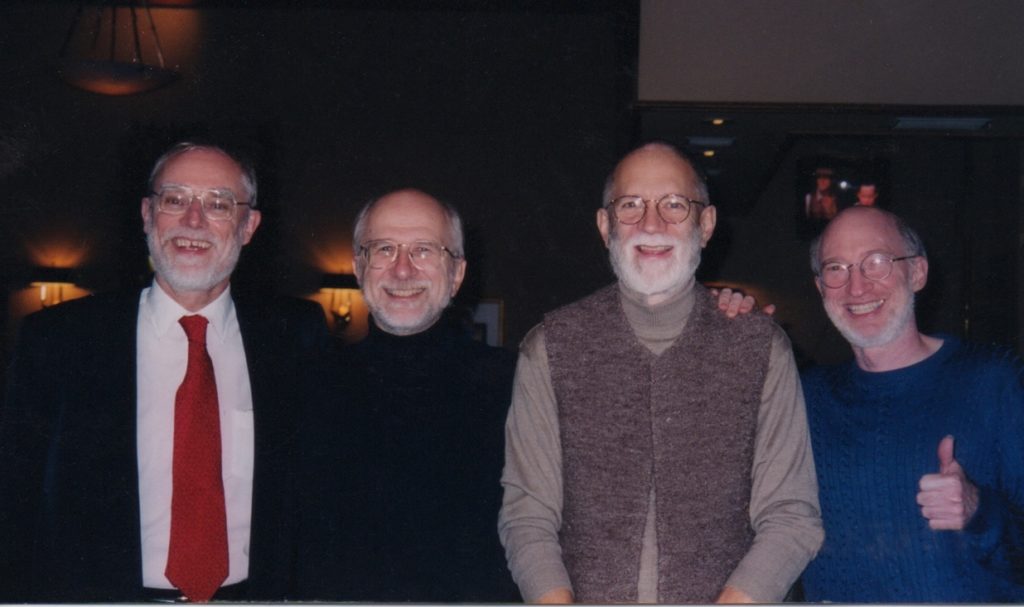

In June of 1974, Jim introduced me to Steve Reich, and on December 17th of that year I played my first concert with Steve, Jim, and Glen Velez at the Jamaica Arts Center. Thanks to Jim, so many of us connected with Steve. As Steve changed the world of music our worlds naturally changed, and I am so grateful to have had this opportunity. Jim was one of the giants of percussion in the center of it all.

One summer, we all traveled up to New Hampshire for a music festival. On an afternoon off, we went to the beach and when we were all ready to leave, Donna realized she lost her wedding ring in the sand. Jim and I went crazy plowing the sand in search of the ring while Donna gently grazed her hand over the sand’s surface. Miraculously, after a few minutes, she found the ring. Donna had just the right touch and her hand was drawn to that ring. Soon after, Jim became a single parent. Yet another lesson Jim provided me – one in fatherhood under extraordinary circumstances. I know that just as Jim was, Donna would be so proud of Jeff and Chris and the men they’ve become. Jim remained devoted to Donna’s memory for the rest of his life. As Donna’s hand was drawn to that ring, we know that Donna and Jim are now finally drawn back to each other and at peace.

When I was young, I thought there would be a time when friendship would transform the student – teacher relationship into a relationship simply between friends. I mistakenly believed that there would be some benefit to not feeling like someone’s student. I am so grateful that Jim showed me differently. Along with being a life-long friend, Jim remained my teacher and my mentor for over 43 years.

Jim Preiss

master musician, master teacher, great friend

whose memory will continue to inspire us all.

In Memory of Jim Preiss – Music and Words by Gary Schall

Gary Schall began performing the music of Steve Reich when he was 16 years old while studying with James Preiss at the Manhattan School of Music Preparatory Division. He performed his first concert with Steve in 1975. At the time he was 19 years old, making him the youngest member of the ensemble. Schall has continued to perform with Steve for over four decades. The depth of this experience had the most profound influence on Schall as a performer and composer.

Excerpt from Music for 18 Musicians, courtesy of www.schallmusic.com

Letter to Steve Reich from Russell Hartenberger following the funeral of Jim Preiss

Dear Steve,

I just returned from NYC to attend Jim’s funeral. It was a simple service in keeping with Jim’s approach to many things. The church was not much more than a two-room store front on Roosevelt Avenue in Queens with an elevated subway track running overhead. One of the rooms was a small chapel where the service was held. The pastor was a young man who said Jim had attended the church for about five or six years. He said Jim often brought timpani and other percussion instruments to play at the church.

Several musicians from the ensemble were there: Liz Lim, Gary Schall, Frank Cassara, Ed Niemann, Dave Van Tieghem, and Todd Reynolds. Unfortunately, Nurit came down with the flu last night and was unable to attend. It’s a shame since she seemed to be the one who tended to Jim the most in his last weeks.

Other musicians from New York were there and I was told that many other percussionists came to the wake yesterday. Jim’s sons, Chris and Jeff, were there, of course, as were his two brothers from Minnesota. The two brothers looked a lot like Jim and had many of his mannerisms. It was kind of surreal to see them. One of them even dressed like Jim did.

Jim’s coffin was open at first, then closed for the service. It was draped with a U. S. flag in honor of his military service. I’m not sure how they arranged to get the flag, but it was just like the kind you see on the coffins of servicemen who have been killed in battle and buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

The service was simple with some Bible verses, a couple of hymns, and a short talk by the pastor. He mentioned the three things Jim loved in life: religion, music, and food. We then caravanned to the cemetery in Kew Gardens for the interment. The pastor read some more Bible verses, then the flag was folded, military style, and handed to Chris and Jeff. Jim’s gravesite is a pleasant spot under a large tree in a relatively quiet part of the cemetery. The weather was very cold and there was a lot of snow on the ground, so we didn’t stay very long at the gravesite. However, just as the short ceremony ended, a beautiful rainbow appeared in the sky.

As ever,

Russell

January 28, 2014